The socio-spatial landscape of what we call the ?in-between city,? includes that part of the urban region that is perceived as not quite traditional city and not quite traditional suburb (Sieverts, 2003). This landscape trepresents a the remarkable new urban form where a large part of metropolitan populations live, work and play. While much attention has been focused on the winning economic clusters of the world economy and the devastated industrial structures of the loser regions, little light has been shed on the urban zones in-between.

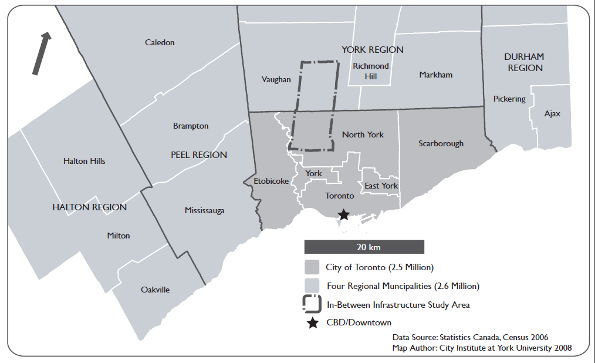

We view this new landscape with a particular view towards urban Canada. Applying these concepts to a North American city, Toronto, Canada, we look specifically at the 85 square kilometers around York University, an area that straddles the line between the traditional suburb and the inner city.

A politics of infrastructure

When we speak of a ?politics of infrastructure?, we refer to a growing awareness that involves political acts that produce the infrastructure policy for urban regions. We therefore follow Colin McFarlane and Jonathan Rutherford?s advice to open up ?the ?black box? of urban infrastructure to explore the ways in which infrastructures, cities and nation states are produced and transformed together?. This ?politicization of infrastructure? involves the understanding of how infrastructure policies and planning are linked to ?the co-evolution of cities and technical networks in a global context? (McFarlane and Rutherford 2008: 365). The politics that produced the (public) modern infrastructural ideal for the centres and the (privatized) modern infrastructural ideals for the peripheries, largely marginalized the role of d the in-between cities of our metropolitan regions. They were left as residual spaces filled by thruways and bypasses.

But the increased significance of these spaces today commands our attention in new and inevitable ways. In this sense, the politics of the in-between city suggests the need for a de-colonization from the forces that built the glamour zones at both ends of its existence: the urban core and the classical suburb or exurb.

The newest ? 2006 ? census figures in Canada reveal that 70 percent of the population live in metropolitan areas (see note). However, within those urban areas they increasingly live outside of urban cores in a new kind of urban landscape. Interestingly, more Canadians also work in the suburban parts of metropolitan areas. The number of people working in central municipalities increased by 5.9 percent from 2001 to 2006 whereas the number of people who worked in suburban municipalities increased by 12.2 percent.

Of course the growth of the traditional suburban kind continues, and while inner cities experience densification of office and condominium developments, much of the most dynamic growth areas are literally in-between. But the picture in the old suburbs and the enclaves is a distinctly mixed one. There are areas of aggressive expansion, for example around suburban York University in Toronto, where a New Urbanist-styled ?Village at York? has added one thousand units of residential space. Yet just one block away, the Jane-Finch district continues to lose both in economic standing and demographically and remains one of the designated ?priority neighbourhoods? where the City of Toronto sees much room for socio-economic improvement.

Yet even as these in-between areas experience fast paced socio-spatial change, the realities of political and administrative power leave them marginalized. The Steeles Avenue corridor at the northern edge of the York University campus, for example, is a major east-west thoroughfare at the border of two municipalities ? Toronto and Vaughan ? that has enjoyed little attention from the cities? investors and resident communities. Planners in the two municipalities have only recently begun to think about redevelopment possibilities in the corridor, but their policy-making is largely in isolation from each other. Just where the need for articulated urban infrastructure development is greatest, the capacity to act is least.

At the same time, the linear nature of public transit and other networked infrastructure which favour either mass concentration of jobs or housing or wealthy suburban enclaves ? leaves many places that lie between designated destinations in a fallow land of unsatisfactory access. This bias is corroborated by the political decision making processes.

No politician, planner or bureaucrat will champion public expenditure in the in-between zone, particularly if they are inhabited by or provide jobs to socially less powerful groups. As a consequence, infrastructure built to connect centres actually disconnect those non-central spaces that lie in-between. While highways link smart centres and movieplexes around the urban region, blue collar workers in the widespread facilities of the sprawling suburban Toronto industrial districts rely on irregular buses or van service to get them to and from work.

Empirically, our 85 sq km study area ? partly in the City of Toronto and partly in the City of Vaughan ? is home to about 150,000 people. It is a place that is rich in social and physical complexities and contradictions. Uneven access to different infrastructure is particularly visible in the poorly understood and under-recognized ?in-between city.? Casting light on the infrastructure problems of the ?in-between city? is a necessary precondition for creating more sustainable and socially just urban regions, and for designing a system of social and cultural infrastructure that meets community needs.

How can renewal come to the politics of infrastructure in the in-between city? The question is how our respones to the global economic recession can effect these oft-neglected regions. Will they reinforce the ways in which the in-between areas and their dependent populations have been marginalized or will they participate in the renewal?

Note: Census Metropolitan Areas are defined as having a population of at least 100,000.

References

McFarlane, Colin and Jonathan Rutherford (2008) Political Infrastructures: Governing and Experiencing the Fabric of the City, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32,2; 363-74.

Sieverts, Tom (2003) Cities Without Cities. Between Place and World, Space and Time, Town and Country. London and New York: Routledge.

Photo by Rick's Pics (Montreal)

Full story at http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/Newgeography/~3/apdCOdsww9M/001497-reconnecting-in-between-city

No comments:

Post a Comment