Census data continue to suggest that fringe areas still grow faster than cities, but some have continued to argue that the flight to the suburbs has ended, or at least slowed, and that we are experiencing a resurgence of urban living. In a 2005 article for the Journal of the American Planning Association, Robert Fishman predicts a new pattern of migration ? a so-called Fifth Migration ? that will revitalize inner core neighborhoods that were depopulated through decades of suburbanization. In a 2004 study of the New York region, James W. Hughes and Joseph J. Seneca contemplate the beginning of a ?third transformation,? or a post-suburban regional geography, characterized by the end of population dispersion and the beginning of recentralization.

Anecdotes, rather than hard data, have tended to drive the back to the city case. Data brought to bear on the issue usually shows the suburbs are still going strong. Yet it also appears that all suburbs are not created equal and population data may be missing subtle population shifts within a metropolitan area. The flow of households within a metropolitan area can show early signs of a change in a region.

This analysis considers the extent to which there is the beginning of a back to the city movement in the Washington DC metropolitan area using county-to-county migration data from the Internal Revenue Service. We must start with the assumption that the Washington area is unique among American metropolitan areas. The presence of the national government largely shapes the structure and geography of the regional economy. A large share of the region?s jobs is concentrated in the core, due to the role of the Federal government in the region. However, in addition to being the seat of the Federal government, the Washington DC metropolitan area also serves a varied set of private sector employers, and is home to a diverse population with growing suburban and city neighborhoods.

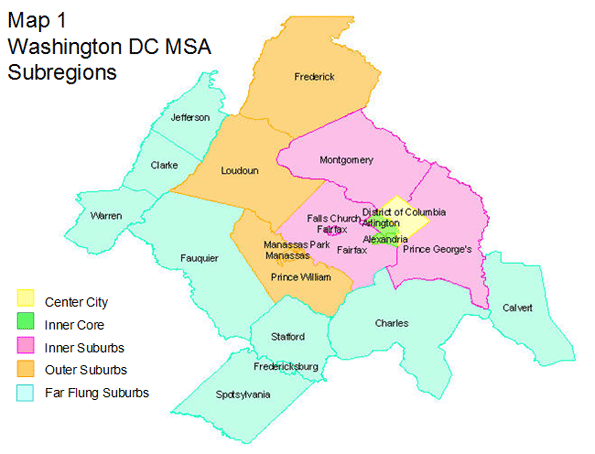

The metro area is defined by 22 counties and cities in the states of Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia and has at its center city the District of Columbia. For this analysis, the Washington DC metropolitan area is divided into five sub regions: Center City, Inner Core, Inner Suburbs, Outer Suburbs and Far Flung Suburbs (see Map 1). According to Census Bureau population estimates, between 1987 and 2007 the population of the Washington DC metropolitan area grew from 3.92 million to 5.31 million people, an increase of about 35.5 percent. The population growth rates over this period varied considerably within the metropolitan area. The Center City experienced a 7.6 percent population decline between 1987 and 2007 while all of the other subregions in the metropolitan area grew. The fastest growing subregion was the Outer Suburbs, where the population grew by 109.6 percent over the 20-year period, followed by the Far Flung Suburbs (80.0%), Inner Suburbs (27.4%) and Inner Core (23.7%).

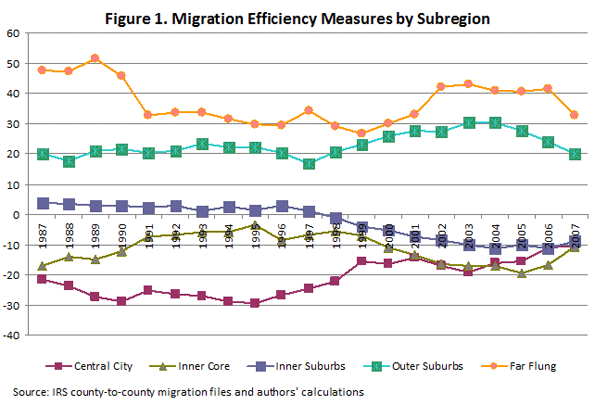

Figure 1 shows that the subregions furthest from the region?s core, the Outer Suburbs and Far Flung Suburbs, consistently have the highest rates of net migration, which indicate that they have been net gainers of households from other parts of the metropolitan area over the past 20 years. For the Inner Suburbs, net migration is positive (but small) until 1998 when it becomes negative. Both the Inner Core and Center City have negative net migration over the entire period, reflecting losses of households to the rest (i.e. the suburban portions) of the metropolitan area.

Looking at the entire 20-year period suggests that the suburbs of the Washington DC metropolitan area have gained population at the expense of the closer-in jurisdictions. However, in the last few years, since 2005, the net migration rates for the Outer Suburbs and Far Flung Suburbs have declined while the rates for the Inner Core and Center City have become less negative. These three years of data suggest that the more distant suburbs have started gaining households more slowly while the closer-in jurisdictions have lost households more slowly with net migration rates moving towards zero. While three years do not necessarily constitute a trend, this analysis suggests the possible beginning of a modest back to the city movement in the Washington DC area.

However, household gains (or a slowdown in losses) in the inner jurisdictions may be coming more at the expense of the Inner Suburbs as opposed to the more distant suburban jurisdictions. The Inner Suburbs subregion is continuing the downward trend in net migration rates that began in the late 1990s, losing households to both the outer suburban and core jurisdictions. If this trend continues, the Washington DC metropolitan area may experience a relative population decline of its Inner Suburbs, while the more far flung suburbs continue to grow (albeit more slowly) and the population of the inner jurisdictions stabilizes or even grows slowly.

Despite the beginning of a small back to the core movement, the suburbs of the national capital region will continue to gather most future growth, and that suburban growth will be even further out. Over the last three decades, jobs have followed people into suburban communities; a place like Tyson?s Corner in Fairfax County now has almost as many jobs as Washington?s downtown business district. Workers can live in the Outer Suburbs and Far Flung Suburbs, benefiting from the relatively lower housing costs and commute with relative ease to jobs in these suburban employment centers. Some share of the population will choose to move back to the city, but there will always be demand for suburban life.

The Inner Suburbs are caught in the middle of population moving in and moving out. The Inner Suburbs have become more urban and congested, as well as more racially and ethnically diverse. These changes may cause some households ? including both native born persons and upwardly mobile immigrants ? to look even further out for a traditional suburban lifestyle. A younger metropolitan area, the result of the large millennial or ?echo boom? generation, may lead to more people moving out of the congested Inner Suburbs to a ?real? urban neighborhood in the core, which is also crowded, but has public transit and walkable communities. This trend, however, may well be short-lived if, when this generation hits their mid-30s by 2015, it acts like previous generations, starting to raise families and move again to suburbs, most likely in the further periphery.

All this suggests, for the short run at least, a possibility that this new pattern of household redistribution could create a new divide in the national capital region. Different from the well-documented east-west divide, the emerging divide will be between the ?urbanites? and the ?far flungs.? The divide will be demographic, economic and political and will characterize the future challenges to forming transportation, housing and other regional policies.

Lisa Sturtevant is an Assistant Research Professor at George Mason University School of Public Policy, Center for Regional Analysis.

Full story at http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/Newgeography/~3/rfU2RJoqJeo/001243-a-return-city-or-a-new-divide-nations-capital-region

No comments:

Post a Comment